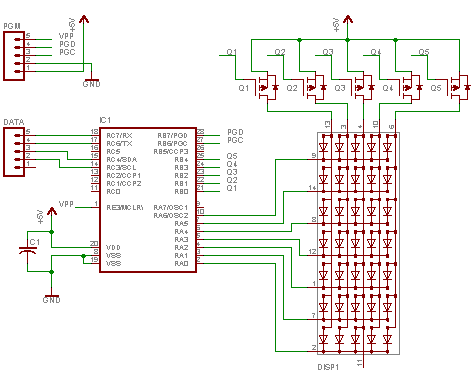

The single character LED sign I had been playing with now has a purpose! Shortly after discarding several ideas of having it as a serial display for PC/Server status, or hooking it up to the internet and a webcam, I came up with an actual useful purpose. The sign can be a clock! I have two ‘modes’ planned; traditional numbers and binary. All geeks love binary clocks, but most of us are lazy and would rather read regular ‘ol numbers.

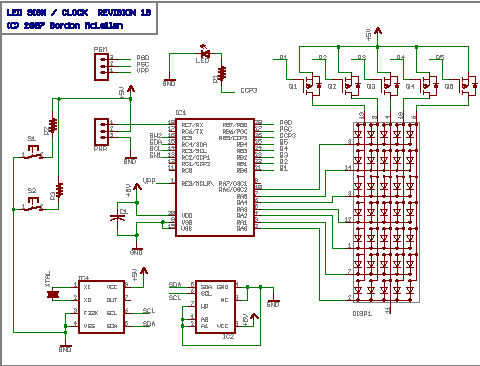

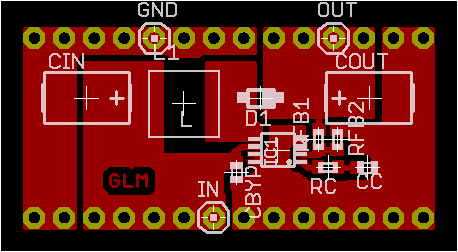

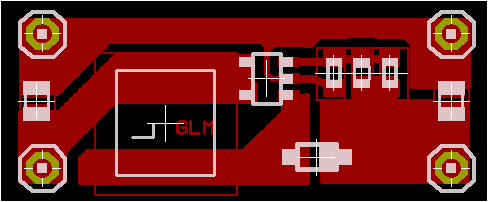

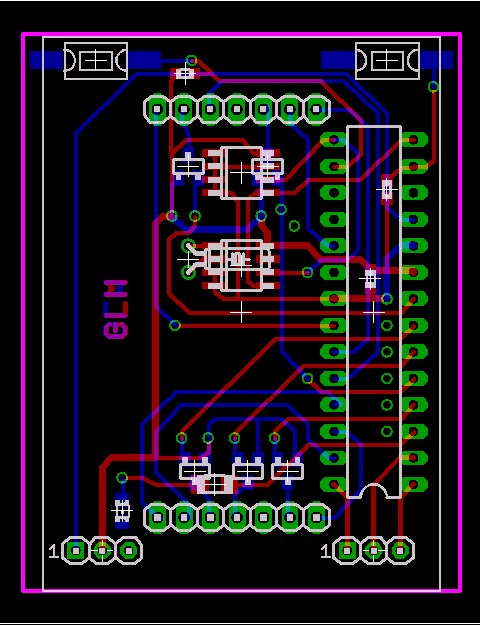

To facilitate the role as an clock, I had to redesign the circuit quite a bit. Two new ICs were added, allowing the LED Sign to keep time, and providing some much needed storage.

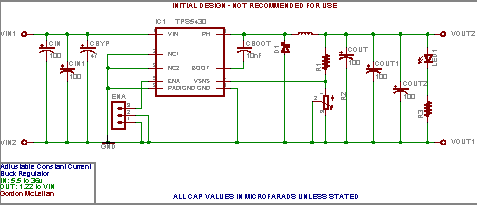

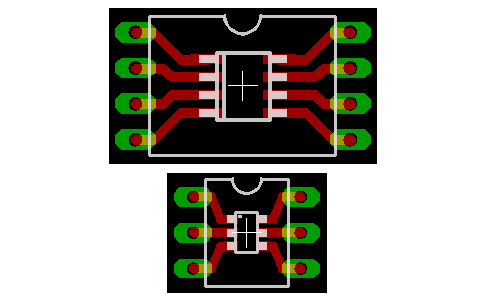

The first of the new ICs is a Real Time Clock. Because I’m cheap, I chose the M41T80 from ST Micro. It’s an inexpensive clock, similar to the Dallas DS1307 but lacking a few minor features. First, the clock has no power-on reset detection. It just starts up as soon as power is supplied. The Dall 1307 has a stop bit which gets set if the clock experiences a POR, so the firmware can test if the clock needs to be initialized or not. The T80 datasheet mentions some registers may get set to default values on power up, so I’ll have to read it a few more times to see if there is a way I can check for a POR. Second, the T80 has no support for a separate backup battery. Instead, ST recommends you place a diode in series with the clock, and use a large capacitor to provide backup power. Last, there is no automatic leap year / leap second correction, oh well!

The second IC is a 16 kilobit serial eeprom, similar to the Microchip 24C16, I chose one from Catalyst semiconductor due to lower costs. The eeprom is arranged as eight banks of 256 bytes each. The chip contains a 16 byte write-buffer, I’m not sure if it can cross a bank boundary or not, I’ll program my firmware assuming it can not. The eeprom will be storing character strings related to operation of the LED Sign as a clock, as well as user programmed messages and possibly simple graphics.

I’ve also added some micro switches for adjusting the clock and changing settings, also a 32.768kHz crystal was added to providing the timing source for the RTC.

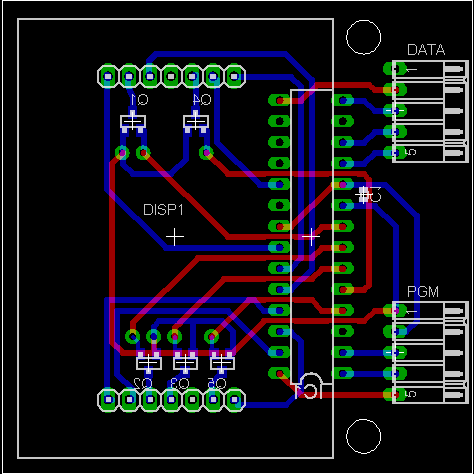

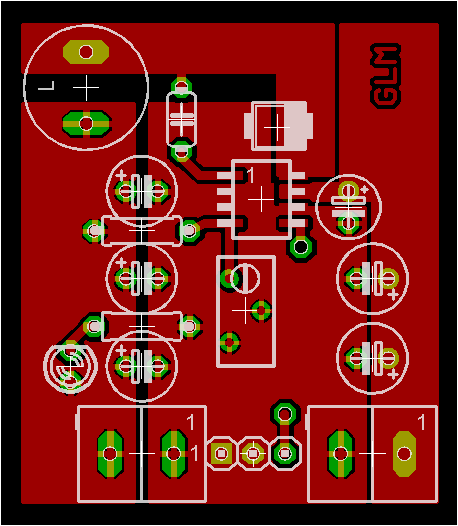

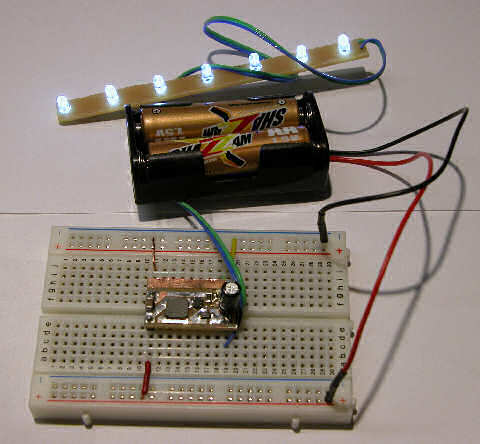

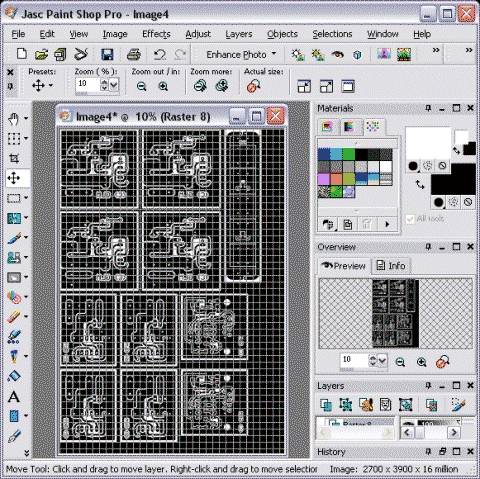

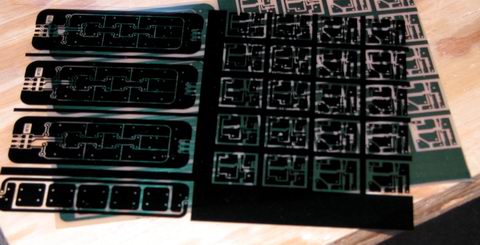

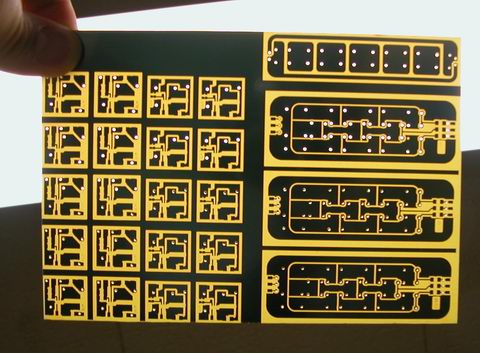

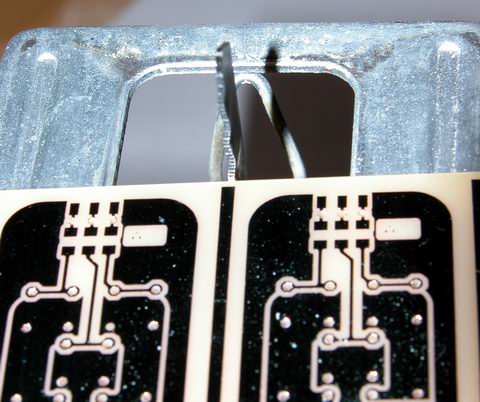

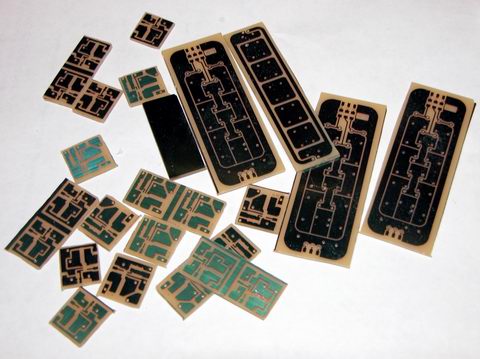

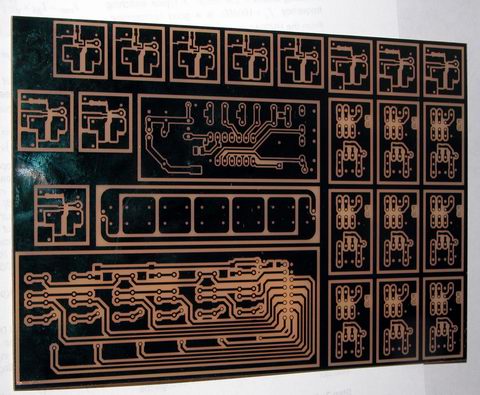

At this point, the layout of the printed circuit board has become pretty complex. I tried making one of these at home, but didn’t have the patience to exactly align the top and bottom layers of my press and peel sandwich. So, I decided to try a pcb prototyping house. There are a lot of board houses to choose from, many of which cost an arm and a leg. All of the domestic board houses are ruled out, I’m sure they do a fine job, but they cost too darn much. I settled on Spark Fun’s BatchPCB service. They’re not the cheapest board house out there, but their cost is fair. They include a lot of features most other board houses charge extra for, like double sided silkscreen and solder mask, 8 mil pitch and spacing, 20 mil holes, etc. I placed my order on the 6th, and had the PCBs by the 22nd. All the time in between, by mind set to wandering, and I made some POV toys. Once the pcbs showed up, I incurred another delay. Turns out I hadn’t ordered my RTC chips yet! So, another few days wait brought goodies from Mouser (man they are quick, and inexpensive!)

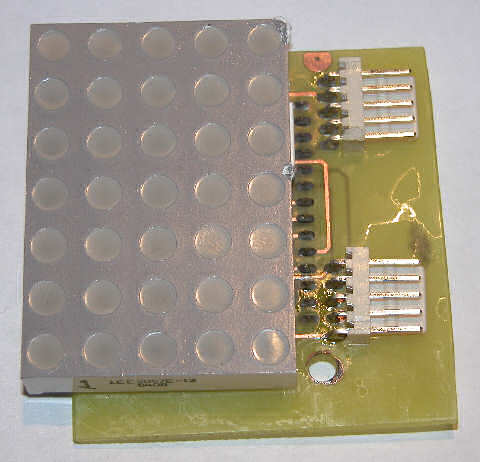

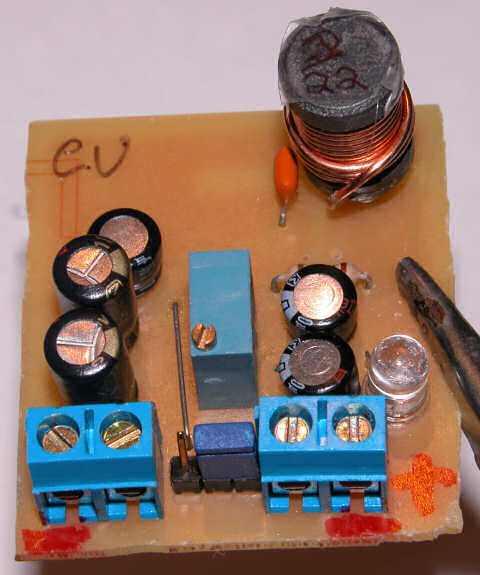

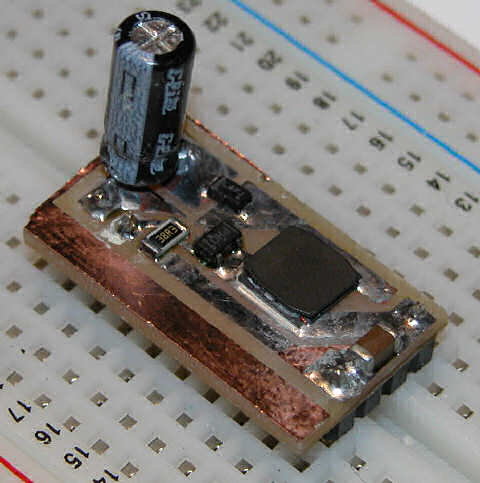

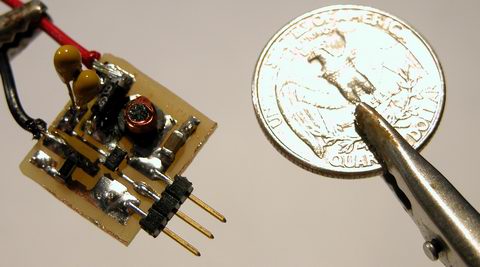

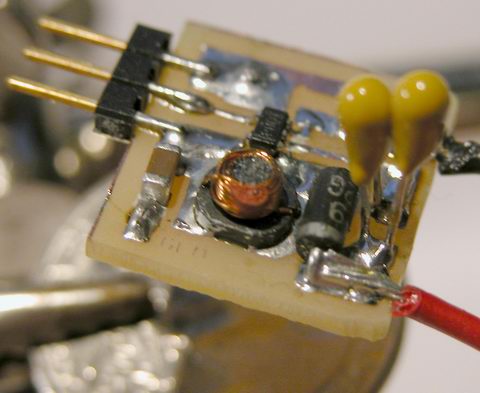

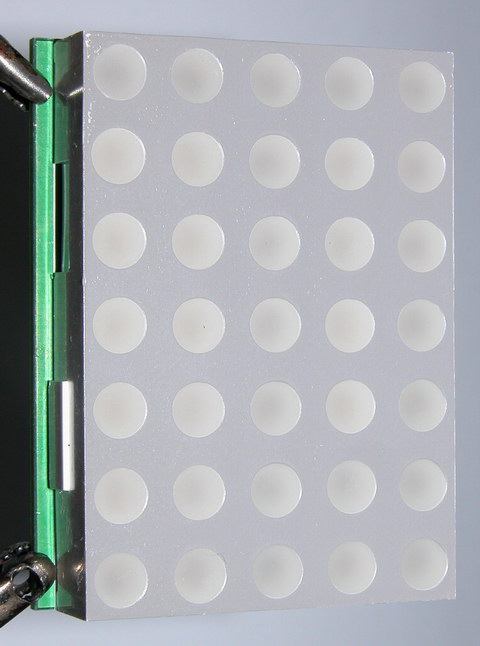

The boards from batchpcb look awesome. Nice bright green solder mask, tinned pads and holes, smooth clean edges. This is the ‘top’ side of my led sign. There are a few passives on this side, along with the two new ICs. This side is covered by the LED matrix once the board is fully assembled. Don’t mind the flux smeared everywhere – I did clean it off before soldering the matrix down.

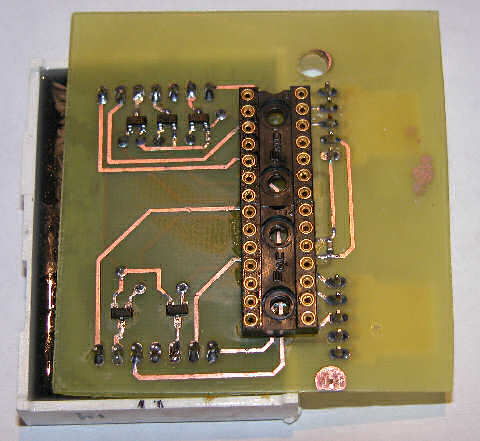

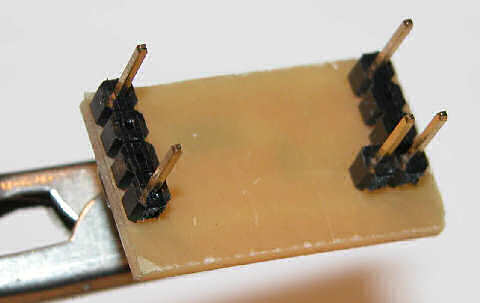

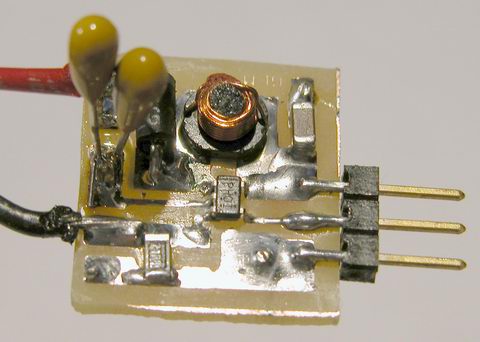

The bottom of the board contains the PIC processor, mosfet column drivers, a crystal for the clock and some microswitches. Pin headers for power and programming the microcontroller have also been installed. The module is a bit thick at this point, thanks to the socketed IC and the pin headers. On the finished version, I’ll solder the IC straight to the circuit board, and probably use wires instead of a header to supply power.

The firmware is in the early stages right now, so my next post on this subject will try to cover whatever features I’ve decided on. Right now I know I want a few things:

1. Scroll the time

2. Occasionally scroll the date

3. Occasionally scroll short messages, either randomly or programmaticlly

4. Support some sort of software brightness control

I’ve made some revisions to the design since I had these boards fabricated. One big oops I made was forgetting the pull-up resistors for the i2c bus! Luckily there’s plenty of room on the board, and both i2c lines ran near the Vcc rail. So a little quick scraping action to peel back the solder mask and presto, new lands for 0603 sides resistors. I’ve also added a diode and big capacitor for the RTC’s backup power.

I hope to work on the firmware more this week, so I should have more details about how the clock works next time!

EDIT: Added a quick video of the time scrolling