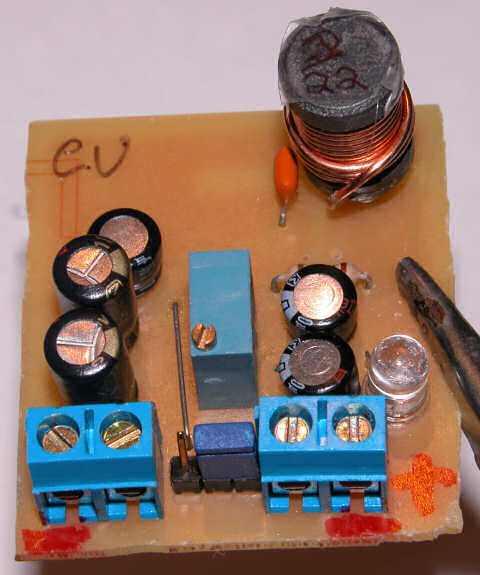

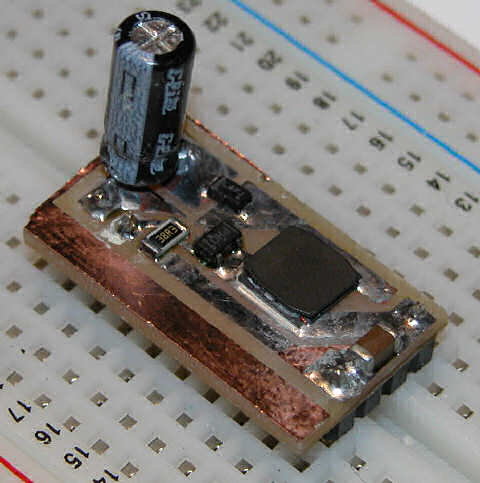

Usually my designs strive to create tiny boards, and I often obsess for days fine-tuning, shaving a fractions of an inch at a time. However, this design goal was get it done, get it working, then make it pretty.

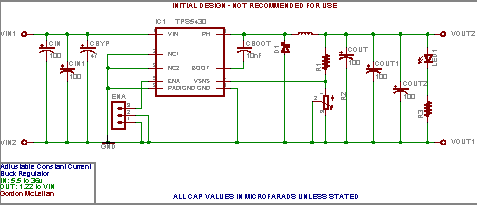

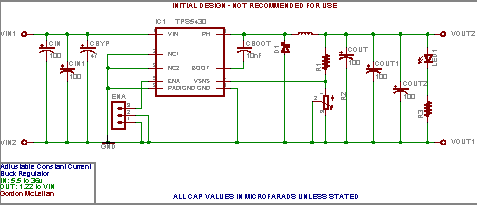

I’ve been trying to build a switcher to provide a portable power source for PDA’s, cell-phones, etc. Not just enough to trickle charge said gizmo for hours, but to charge it as fast as possible, like the cradle or wall plug would do. This requires quite a bit of power. Packaging portable power is proving very tricky. There’s two main design goals I’m trying to meet. My primary goal the past week has been recharging the power-source, and the easiest way to do this is parallel cells. There’s oodles of charge management chips out there designed to handle charging of single lithium-ion cells (or parallel cells). The complexity knob gets turned WAY up once you start talking series cells. So rather than spin my wheels on this problem, I chose to move forward with goal number two. My secondary design goal is to get the power out. Putting the cells in series opens a wide door for easy to use switchmode converters and controllers. I’ve got a bin full of samples from all the big names, and I’m close to settling on a chip. First to prototype is the TPS5430 from Texas Instruments. This chip claims to have a three-amp switch on board, and it’s pretty easy to use. The switcher is internally compensated, eliminating an RC network often needed to compensate high frequency switchers. The 5430 comes in fixed voltage models, but I went with adjustable this time.

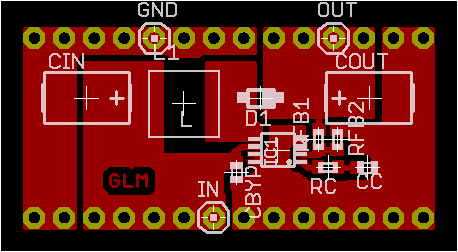

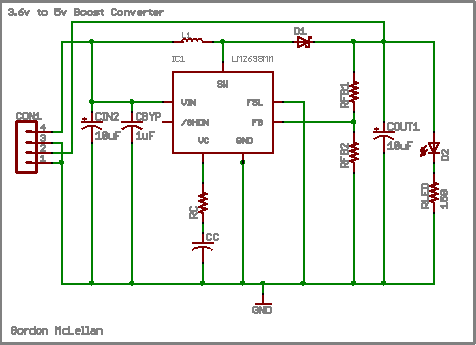

Using TI’s SwiftDesigner to generate a reference design, I drew that up in Eagle. Their reference design specified solid tantalum capacitors, which have properties that lend themselves well to switchmode applications. However, having priced 100+ uF tantalum caps, I’ve decided to use aluminum electrolytic instead. To offset some of the short-comings of aluminum caps, I have connected several in parallel. The main disadvantage is ESR, and wiring caps in parallel cuts the ESR dramatically.

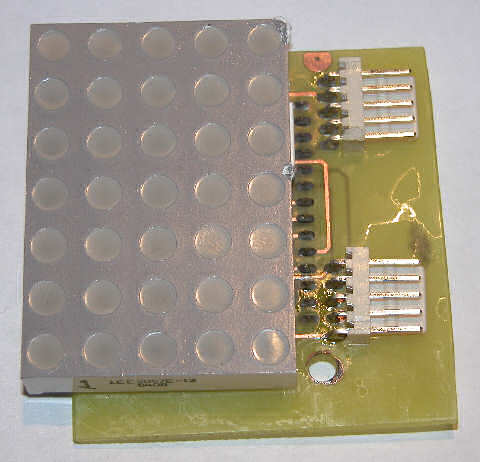

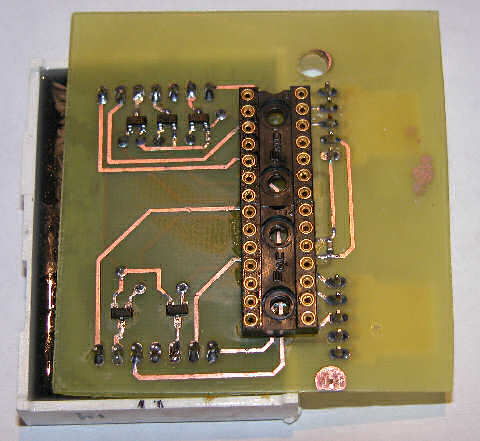

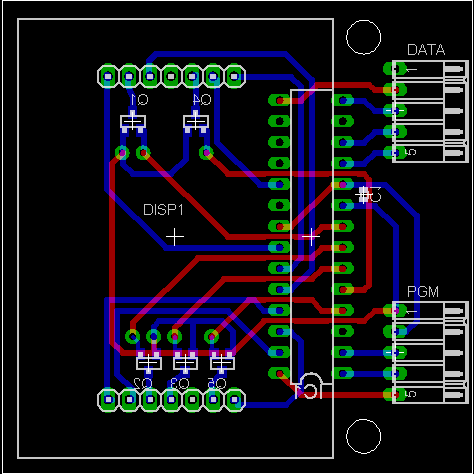

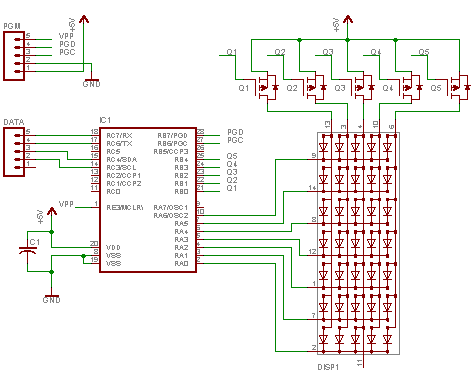

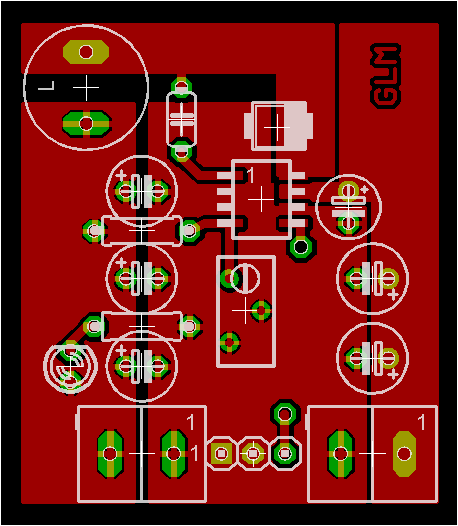

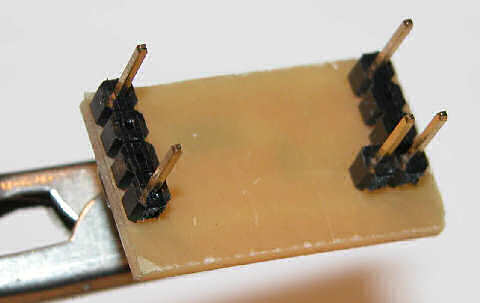

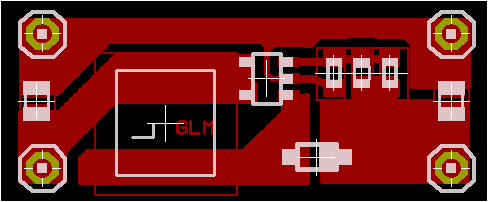

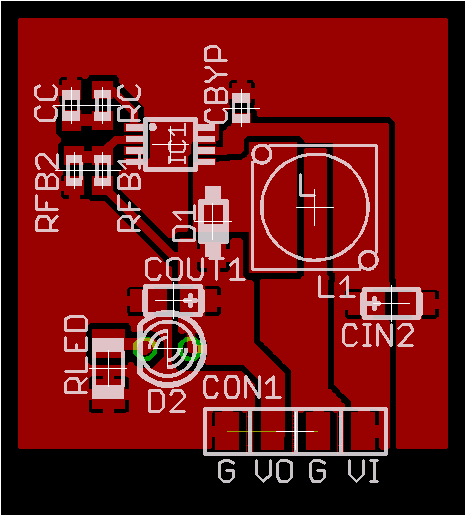

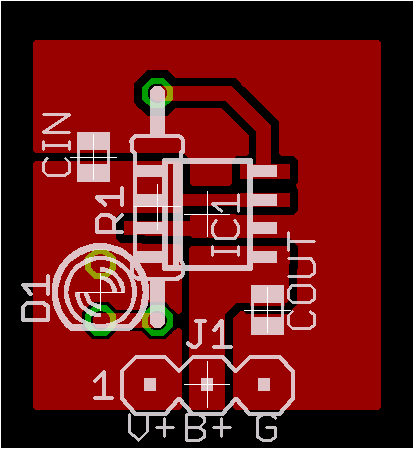

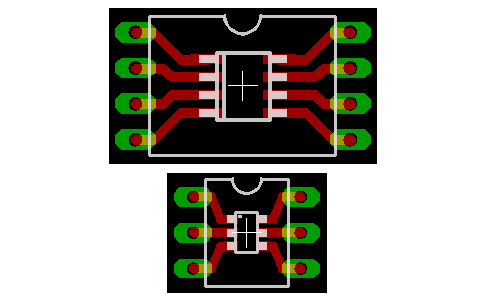

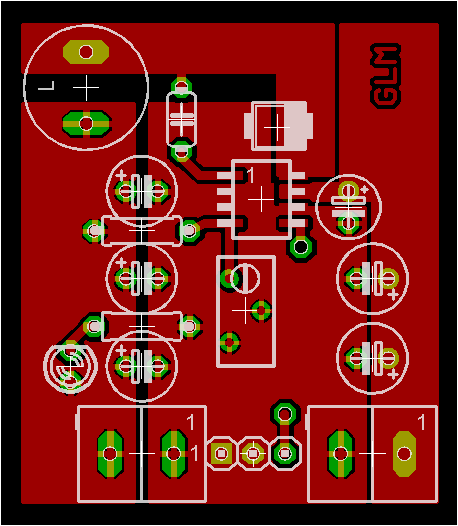

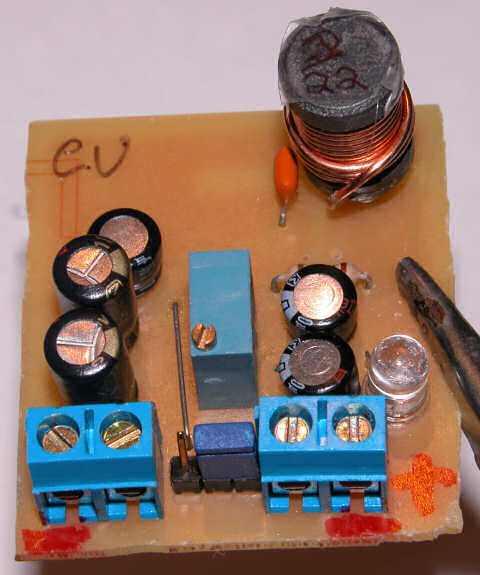

Loosely following TI’s reference layout, I came up with this design. I drew the design using the top layer, and ended up flipping it over when I assembled it. It doesn’t really make a big difference, just as long I remember to solder everything in a mirror image of what’s shown on the screen. For example, the screen shows the input stage on the right, but on the prototype, the input stage is on the left. The reference design called for a single 100uF solid tantalum capacitor rated at 25 volts (I spec’d 14v as VinMax). It also called for a 47uF tant as a bypass cap for the IC. So instead, I went with two 100uF 25v electrolytic caps and one 47uF 16v cap. I realize 16v is cutting it a bit close, but it’s all I could come up with, and this is only a first pass. The output stage called for a single 220uF 10v tant, instead, I drew room for three 100uF caps but only installed two for now. The chip needs a bootstrap cap to help it start-up with low input voltages. The datasheet called for 10nF, so thats what I used. The voltage divider is a 10k resistor coupled with a 10k pot. A resistor and LED were added to show “power on”. The three pin terminal at the bottom is tied to the enable line. Enable should float for normal operation and be pulled low for shutdown. I used a big ‘ol coil I had laying in the parts bin, it was labeled 22uH but the actual inductor is not marked. Looking at the size of the bobbin and heft of the wire, I’d say this inductor can handle some serious current. A three amp schottky diode completes this bit of kit.

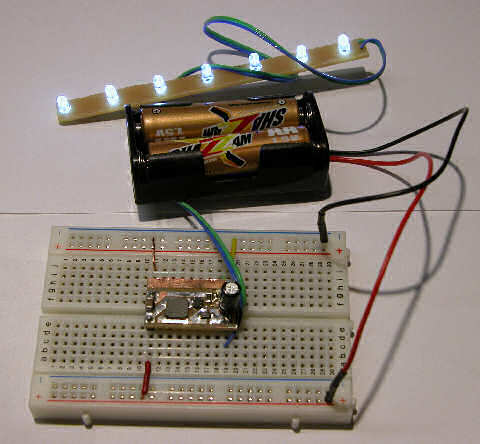

With one set of fingers crossed, I hooked the switcher up to a wimpy 200mA 12v wall-wart, used for charging a screwdriver. To my relief the LED came on, nothing started smoking, and the ammeter read 10mA on the 10a scale (later I re-read 13.59mA on the 20mA scale). The datasheet claims 3-4mA of quiescent current, so the switcher is taking 10mA at 12v to supply 20mA at 5v. Although I haven’t done the algebra in the datasheet, comparing watts in to watts out puts the efficiency in the not-bad to pretty good range. (100mw / 120mw = 83%). Better still, when I connected my Dell PDA to the switcher, it was able to supply as much current as the Dell could ask for, without raising above ambient temperature. With a low internal battery, cpu set to 400mhz, external wifi card inserted, backlight full-on, the Dell peaked at 1.1 amps. I left it laying on the bench and watched a movie for a few hours. Coming back, the dell was completely charged, and the output had dropped to about 170mA.

My next goal will be to miniaturize this circuit as best I can, hopefully to fit it into an altoids tin which holds my lithium cells so very nicely.